In The Magician’s Nephew, the Wood Between the Worlds was a mysterious inter-dimensional realm from which people could magically travel from one dimension to another. It is from this realm that Digory Kirke and Polly Plummer first encountered Charn, home world of the White Witch, and, later, Narnia.

The cross is the wood between the worlds—the world that was and the world to come.

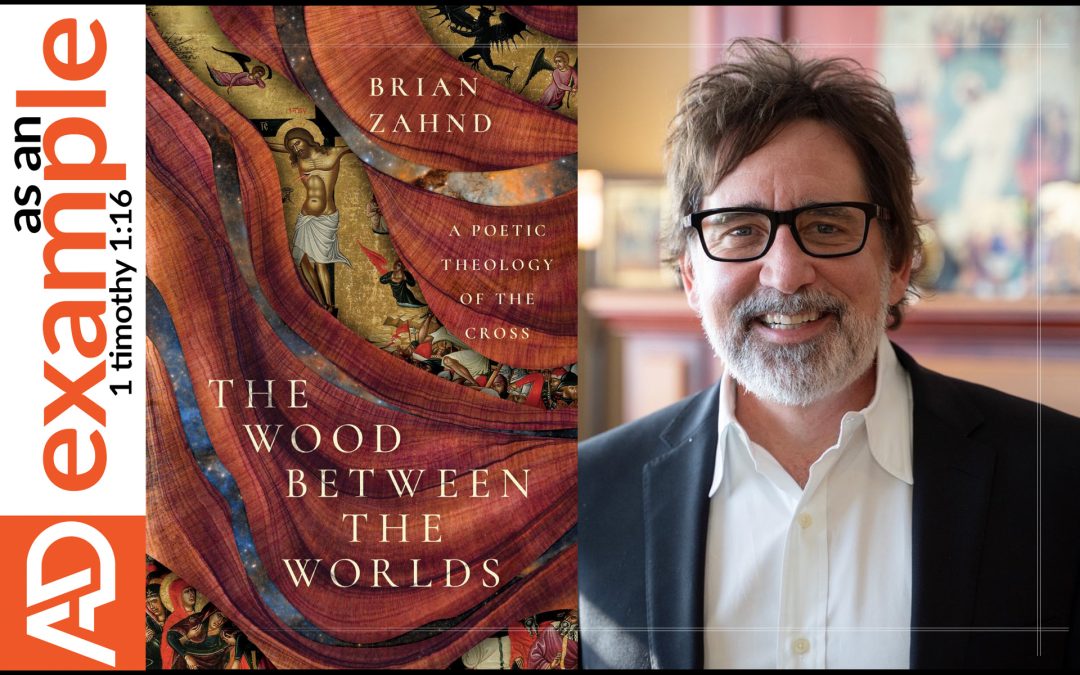

Brian Zahnd draws on this imagery as the inspiration for the title of his book of essays reflecting on the cross. “The cross,” he writes, “is the wood between the worlds—the world that was and the world to come.” The cross changed everything. In this book, Zahnd offers a multifaceted theology of the cross and how it changed the world. He admits, as will every Christian, that the riches of the cross can never be fully exhausted, but each chapter addresses a particular aspect of the cross and how it changed the world.

I had not read much of Brian Zahnd prior to this. I was vaguely aware that he is more rooted in the “progressive” camp of Christianity than I am. Indeed, he describes himself as “a Protestant by default” and a “deeply ecumenical Christian” who feels “quite at home worshiping with Orthodox and Catholic believers.” Since I am a Protestant by conviction rather than default, with serious differences with Orthodox and Catholic churches (notwithstanding the number of true believers I imagine to be present in those churches), I opened this book with a sense of caution.

Almost immediately, I was struck by Zahnd’s writing skill. His prose, at least in this book, is almost poetic. Indeed, he describes his style in this book as “theopoetics,” which he defines as “an attempt to speak of the divine in more poetic language. It is an attempt to rise above the full and prosaic world of matter-of-fact dogma that tends to shuts down further conversation.” In terms of writing style, he certainly accomplishes this goal.

He clearly articulates his belief that the cross changes everything by addressing some matters that might be considered “thorny.” He shows how the message of the cross contradicts much of the evangelical church’s thirst for political power. He argues that the message of the cross is inconsistent with modern warfare and calls Christians to a position of cruciform nonviolence. He maintains that the message of the cross cannot be reconciled with support for capital punishment. He discusses the typological connection, often missed by Christians, between the cross and the lynching tree of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries in the American south. He is aware that these connections will raise the ire of some readers, but he is unafraid to confront them.

We keep thinking that political power is a gift instead of realizing that it is a poison that will eventually corrupt us.

There is beyond dispute a fair amount of beneficially thought-provoking material to be found in the book. Chapter 10, which addresses the inconsistencies between the message of Christ crucified and the seeming thirst of many evangelicals for political power, is excellent. While many evangelicals embraced Donald Trump’s promise of Christian power if he was elected as President, Zahnd cautions, “We keep thinking that political power is a gift instead of realizing that it is a poison that will eventually corrupt us.” The church has power, but it is not the power that politics promises. The church’s power resides in the power of forgiveness and the power of the Holy Spirit, not in political power.

His argument for nonviolence in chapter 11 is brief and, if not entirely convincing, should at least serve as a conversation starter. He argues strongly that the cross puts to death any justification for Christians engaging in warfare. Baptism, he argues, marks one as a citizen of God’s kingdom, and citizens of God’s kingdom do not engage in the satanic act of war. “The sins of violent hostility were sinned with violence into the body of Jesus. But when Jesus absorbed and forgave this violent hostility, war was abolished.” Augustine’s just war theory does not hold up under scrutiny, he argues. “Today, all war is total war and Just War is just war.” His thoughts will hardly end the discussion surrounding warfare and nonviolence, but it ought certainly to spark it.

In my mind, one of the book’s major weaknesses is the author’s seeming cherry picking of texts that strengthen his case. For example, in his discussion on the Christian and warfare, he addresses Revelation 19’s rider on the white horse to show that it does not portray Christ returning as a warring judge. However, he does not touch on more didactic texts which seem to present the same theology that, according to him, Revelation 19 does not. It might serve him well, for example, to address a text like 2 Thessalonians 1:5–10, which speaks of Christ returning “in flaming fire, inflicting vengeance on those who do not know God and on those who do not obey the gospel of our Lord Jesus Christ.” Even if his exegesis of Revelation 19 is compelling, it weakens his overall case to overlook other obvious texts that might challenge his position.

Another somewhat ironic weakness is his use of the very same tactics that he denounces. While he complains early in the book about “the full and prosaic world of matter-of-fact dogma that tends to shuts down further conversation,” he appears to engage in a fair amount of such dogma himself.

In his treatment of penal substitutionary atonement, a theology of the cross affirmed by a large segment of the Christian church, he brushes the atonement theory aside with words that offer little room for conversation: “Are we to imagine that John 3:16 actually means that God to hated the world that he killed his only begotten Son?” He goes as far as to blame the race-based lynchings of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries on the doctrine. Penal substitutionary atonement, he believes—or, at least the caricatured version of penal substitutionary atonement that he presents—is pagan, which seems to be a very matter-of-fact dogma that tends to shut down further conversation.

He is similarly dogmatic in his appeal for nonviolence, a theology hardly universally affirmed by Christians. He argues that the pre-Augustinian church was aligned in its opposition to warfare. “To renounce war was as much an ethical imperative required by their Christian faith as the renunciation of idolatry and fornication.” Warfare belongs to the world before the cross and “the baptized do not cling to the disappearing past but embrace the emerging future.” Those who interpret the white horse rider in Revelation 19 as Christ the warrior “interpret the Christ of the Apocalypse as radically other than the Christ of the Sermon on the Mount,” which is “a pernicious interpretation of the text.” It does little good, it seems to me, to complain of others shutting down conversation and then to do much the same thing yourself.

His treatment of capital punishment is, to my mind, uncompelling, largely because he dismisses Old Testament support for capital punishment as inadequate biblical support for the practice. The Old Testament points to Christ and therefore “Christians start their reading of the Bible with Christ, not the Torah.” If we will find support for capital punishment, therefore, it must be found in Christ, not the Old Testament. “The question isn’t whether we can find it in the Bible, but whether we can find it in Christ.” He appeals to Jewish and early Christian distaste for capital punishment as evidence that Christians should oppose the practice and commends the Catholic Church for its opposition of the death penalty. He considers capital punishment to be vengeance rather than justice and suggests that support for capital punishment ignores the image of God in all humans, which seems strange since the Old Testament roots its support for capital punishment in the very fact that humans bear God’s image (Genesis 9:6). He adds that far too many people have been found guilty of capital crimes who have later proven, in fact, to be innocent. While his argumentation might well display the flaws of capital punishment as it is practiced in the United States today, he falls short, I think, of compellingly arguing that the New Testament does away with the Old Testament commands in this regard.

At times, Zahnd meanders. At times, he caricatures. At times, he obfuscates. Readers who already have an aversion toward him may be tempted to dismiss the entire work out of hand. Those who deeply appreciate his ministry might be tempted to embrace it uncritically. In truth, though I opened the book as a reader reasonably squarely in the former camp, I found that there is some good to be found here for those who are able to read with a spiritually mature and critical eye, even if there is a great deal of bathwater that must be drained for the sake of the baby.

Ultimately, I find it a difficult book to recommend, though it certainly contains a degree of helpful, Christological content. There is always need in our reading to chew the proverbial meat while picking out the proverbial bones, but there may be many more bones here than one might typically want in one’s steady diet.